Collectors work with errors for many reasons. Some enjoy the variety of shapes and forms. Others study how production flaws appear on different metals and denominations.

Many now use a coin scanner app to classify coins quickly before sorting them by type. It helps with basic data, yet recognition of true mint errors still depends on visual inspection.

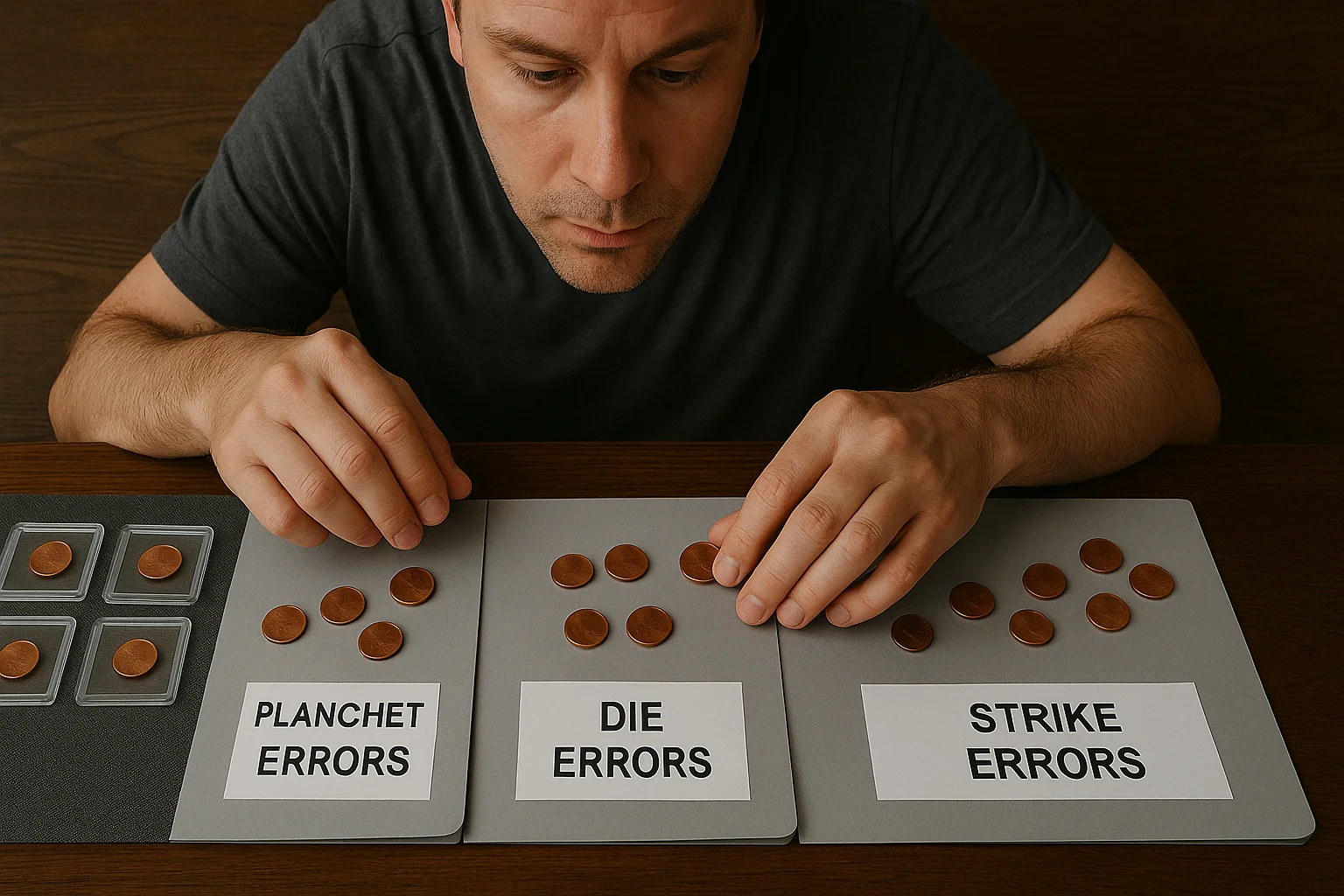

Errors follow physical rules. They come from planchet defects, die failures, or issues during the strike itself. A clear framework makes the process easier and turns a scattered group of odd coins into a structured set with purpose.

Here we would like to make clear how to identify major error classes, what traits define each group, which well-known U.S. examples belong to them, and how to build a themed error collection that grows logically over time.

Why Error Themes Matter

Error collecting becomes simpler when you work with a structure instead of random finds. Most errors fall into predictable groups. Planchet flaws show up before the strike. Die problems appear after repeated use or damage. Strike mistakes happen when alignment, pressure, or planchet position shifts. These patterns help reduce confusion and guide decisions about authenticity.

Themes also help with learning. Handling examples from the same error family trains the eye faster than comparing unrelated pieces. A focused set encourages clear diagnostics, steady progress, and fewer misidentifications.

Core Error Types Worth Building a Theme Around

Mint errors fall into several predictable groups. Each group forms a clear pattern based on when the flaw appears — before striking, during die preparation, or at the moment of the strike.

Understanding these categories helps identify errors faster and gives structure to a themed collection. The examples below show the main types, their visual traits, and well-known U.S. coins that illustrate how each error develops.

Planchet Errors

Planchet errors happen before the strike. The metal blank itself carries the defect. These flaws influence texture, shape, and relief.

Examples and Traits

| Error Type | What You See | Example U.S. Coins | Notes |

| Lamination defect | Peeling, split metal, lifted flake | 1943 Steel Cent with peeling surface; 1950s Wheat cents with lifted strips | Caused by impurities or improper alloy bonding. Metal lifts but stays attached. |

| Clipped planchet | Straight or curved missing section; weak rim opposite the clip | 1964-D Lincoln cent curved clip; Jefferson nickel straight clip | The shape reveals the punch misfeed. The Blakesley effect (weak rim opposite) confirms authenticity. |

| Wrong planchet | Weight and color mismatch; incomplete strike around edges | Cent struck on dime planchet (red-brown cent details on silver-colored blank) | One of the most popular planchet errors. The weight test confirms the mismatch. |

Planchet errors form a strong theme because the flaws occur before any striking force is applied. They also vary widely, which helps build a visually diverse set.

Die Errors

Die errors occur when the minting dies crack, chip, shift, or fail. They produce repeating marks that appear on every coin struck afterward.

Examples and Traits

| Error Type | What You See | Example U.S. Coins | Notes |

| Die cracks/breaks/cuds | Raised lines (cracks) or missing die sections producing blobs (cuds) | 2005 Kansas “IN GOD WE RUST” die break; Washington quarter cuds of various sizes | Cracks increase with die wear. Cuds show where a die fragment fell out. |

| Die chips | Small raised bumps in recessed areas | 2014-P Jefferson nickel with chipped steps; “BIE” Lincoln cent chips | Common and easy to spot. Good for starting a die-state study. |

| Misaligned dies | One side shifted; uneven rim; design off-center | Misaligned obverse cents from the 1990s; quarters with tilted obverse die | Only one side moves. The other remains normally centered. |

| Doubled dies | True doubled design in raised relief; separation lines | 1955 Lincoln Cent; 1972 DDO; 1995 DDO; 2006 Lincoln DDO | True doubling is in the die itself. It must not be confused with machine doubling. |

Die errors are ideal for educational sets because they showcase tool wear and damage over time.

Strike Errors

Strike errors happen during the act of striking. They depend on pressure, alignment, and planchet position.

Examples and Traits

| Error Type | How It Looks | Example U.S. Coins | Notes |

| Off-center strike | Design shifted away from the center | 1970s Lincoln cents 10–40% off-center; 1999 off-center Delaware quarter | A percentage defines a value. Full date increases demand. |

| Broadstrike | Expanded diameter; no collar marks | 1990s Roosevelt dimes struck out of the collar | Metal flows outward, creating a wide coin. |

| Multiple strike | Two or more impressions; overlapping relief | Double-struck Lincoln cents; state quarters with rotated second strike | Dramatic appearance, highly collectible. |

| Weak strike | Soft details; incomplete high points | 1960s Jefferson nickels with flat steps | Often mistaken for wear. Metal flow is the key indicator. |

Strike errors show how pressure and positioning influence the final design.

Design Transfer Errors and Complex Striking Issues

These errors form dramatic, visually unique pieces. They help anchor a themed collection.

Examples and Traits

| Error Type | Description | Example U.S. Coins | Notes |

| Die cap | Coin sticks to die and forms a cup shape, striking more coins | Lincoln cent die caps from the 2000s | Produces deep distortions and stretched relief. |

| Indent strike | Another planchet or object partially covers the coin during strike | Indent cents showing clear circular depressions | Leaves a clean, concave impression. |

| Brockage | Mirror-image design, either full or partial | Large brockage Lincoln cents; Jefferson nickel brockages | Caused by a struck coin sticking to a die surface. Very popular with specialists. |

These errors work well as a standalone mini-collection due to their dramatic and unusual appearance.

Tools and Techniques for Accurate Identification

Error identification requires both observation and structure. Lighting reveals texture. Rotation shows metal flow. Weight and diameter checks confirm mismatched planchets. Consistency helps reduce misinterpretations.

Apps help maintain records. Notes about the die stage, clip shape, or strike percentage become clear over time. So, let us describe in detail.

Can the App Help?

Modern collectors often start with digital tools. A scan gives basic details: denomination, country, date range, composition, and common market category. This saves time and organizes the workflow. Identification of mint errors, however, still requires physical observation. Software recognizes official types, not mechanical irregularities.

The best coin identifier app for iPhone supports sorting, cataloging, and noting the context in which an error appears. Apps help track progress and prevent duplicates, but the surface itself carries the final information.

Relief, rim shape, metal flow, and strike distortion cannot be measured by the camera alone. The reliable tools, like Coin ID Scanner, provide fast cataloging, but confirmation of errors must come from hands-on inspection.

How to Build a Practical Error Collection

A themed error set grows faster when you begin with pieces that show clear, repeatable traits. Early examples teach you how metal behaves, how dies fail, and how misalignment affects the design. The goal is not to chase rare items, but to build a foundation that helps you recognize patterns without guessing.

A strong starting group includes coins that illustrate common forms of damage inside the mint. These pieces are affordable and easy to compare with one another.

Good beginner choices include:

- Lincoln cents with small die chips, often found between letters or inside the date. They teach how raised defects form in recessed areas.

- Minor die cracks on 1990s cents, which show how stress lines develop as the die wears.

- Small cuds on State Quarters, which help you see where a piece of the die broke away.

- Off-center Roosevelt dimes in the 5–10% range, which demonstrate controlled strike displacement.

- Weak-strike Jefferson nickels, where flattened steps show what happens when pressure or alignment shifts.

These pieces build a visual vocabulary. After handling them, complex errors become easier to diagnose because you already know how normal failure stages look.

Short FAQ for Error Collectors

- How do I know an error is real?

Raised features usually mean die damage. Missing metal or depressions often show planchet or strike issues. Compare with verified examples and check for repeating shapes.

- Can software detect errors?

Apps identify coin type and date, but error recognition still depends on surface detail and relief behavior visible under light.

- Should cleaned coins be included in an error set?

Only if the error is strong and the cleaning did not remove key markers. Altered surfaces reduce value and distort diagnostics.

- Are minor errors worth keeping?

Yes. Small cracks, chips, and clips help train the eye and build context for larger pieces.

Final Notes

Error collecting grows from simple observation. Each coin shows how metal moves, how dies age, and how alignment shapes the final design. A clear structure helps these patterns stand out and turns casual finds into a focused set.

Digital tools keep records organized, and a coin scanner app for Android and iOS helps track dates and types, but the final judgment always comes from what you see on the surface. Steady practice builds accuracy, confidence, and a collection that reflects real understanding of how mint errors form.